Ei’ichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professor of Japanese Studies and Professor of History, University of Missouri-St. Louis

Derived from the Latin term appropriare, “to make one’s own,” appropriation is the taking of cultural forms or elements from one setting for use in a different setting. There are multiple meanings of the concept in different academic disciplines, but this entry uses the concept of appropriation to mean a type of borrowing and adaptation that occurs within the confines of one historical group.

A considerable body of scholarship examines a spectrum of appropriation types, tracing the conditions that frame acts of appropriation (for an overview, see Rogers 2006). The concept began as a neutral way to talk about the borrowing or diffusion of cultural elements from one group to another. It was eventually modified in media studies, cultural studies, ethnic studies, ethnomusicology, art history, anthropology, and other disciplines when used as “cultural appropriation.” Cultural appropriation is best known as the taking of intellectual property, rituals, clothing, artifacts, or other elements within a context of colonization or unequal power relations. It refers to inappropriate acts by a dominant group in which the borrowed elements are used for profit, consumption, or fetishization (Ziff and Rao 1997). Consider the insensitivity of two white American bottling distributors who appropriated the name Crazy Horse, a revered Ogala Lakota hero, as a catchy brand for their malt liquor (Newton 1997). Within cultural studies, appropriation is also used to describe the taking of popular culture elements for resistive or subversive ends (Fiske 1989). Among fans of popular culture, we find that appropriation of characters and themes allows them to play with these in ways that are most satisfying for their own pleasure and goals. For example, Jenkins (1988) pointed out that female fans of Star Trek seized on aspects of the television program that appealed to them but amended or transformed the parts they did not like, resulting in new forms such as slash fiction that paired Kirk and Spock in romantic relationships. Acts of appropriation from a dominant or mainstream group by a subcultural or minority group may also subvert meanings through creolization and hybridity (Mercer 1987).

One fascinating trend in Japan is appropriation not from an outside cultural tradition but from its own long cultural history. One example of this is a famous court magician named Abe no Seimei (921–1005), who is found in numerous contemporary cultural productions and settings. Unlike the situation with Crazy Horse and malt liquor, the changes to this historic person’s image through appropriation is occurring within his own descendent society. The social norms and material culture of the Heian period (794–1185) would be akin to an exotic “other” culture for today’s Japanese. Although the world of Seimei’s time would be quite alien, there is rarely debate about whether or not degradation of folktales or damage to his image occurs though appropriation. On the contrary, historians and custodians of his legacy are often bemused or pleased to see a revival of interest in Seimei through popular culture. Interest in historic figures often proves to be lucrative, as Sugawa-Shimada (2015) found when she examined the tourism industry that developed as a response to young female fans, dubbed rekijo (history fan girls), who went looking for traces of the beautiful men of history featured in video games, manga, and other media.

The Heian court included a formal office of court magicians, which was responsible for regulating divination, charting the calendar, and exorcism. Members of this bureaucracy were called onmyōji (wizard, literally yin-yang master). We know about Seimei from medieval folktales in which he was celebrated for his mastery of various occult sciences. Since the 1990s, culture producers and fans have actively appropriated Seimei by creatively modifying his story and imagery (Miller 2008).[1] He became the focus of intense cultural vigor and starred in two major feature films (Takita 2001, 2003). The first film in the series, Onmyōji (The yin-yang master) starred handsome actor Nomura Mansai as Seimei and was a commercial success, ranking fourth among all films the year of its release. Seimei also became the central character in several television programs, including a ten-episode series in which Inagaki Goro, former member of the boy band SMAP, was cast in the lead role (Odagiri 2001). In a special made-for television movie, a Kabuki actor named Ichikawa Somegoro was cast as Seimei (Yamashita 2015). Seimei is also found as a character in music videos, books, computer games, and countless manga and anime.

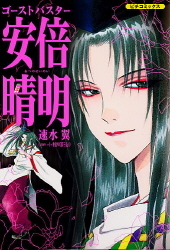

Ghost Buster Abe no Seimei (Hayami and Koyanagi 2003).

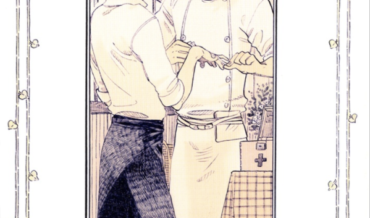

Although Seimei appears widely in a spectrum of current media, this entry will focus on his beautified appearance in manga aimed at girls and women, his commodification by a Shintō shrine dedicated to him, and his adoption by the occult and divination industry. One reason a medieval wizard became a modern icon and folk celebrity in Japan is the manner in which contemporary artists and fans have gone about representing him. Because control of Seimei’s images and stories no longer resides in the hands of elite scribes or historians, anyone—filmmakers, manga artists, fans, and others—may appropriate him and freely imagine him in widespread ways. Even a Shintō shrine devoted to him has participated in this endeavor. For centuries, Seimei was pictured in medieval statues and paintings as a middle-aged man with a large round face and thin eyes, reflecting Heian-era notions of attractive masculinity. Men of that era wore their hair in a ponytail on top on their head, covered by a lacquered court hat (kanmuri). Current aesthetic tastes and the desires of girls and women nourished on boys’ love and romantic comics are clearly encoded in manga and anime representations of Seimei. His long hair streams out from under his formal headdress and frames his angular jaw. An example is seen in the manga Ghost Buster Abe no Seimei (Hayami and Koyanagi 2003). These new images of Seimei reconcile his historical persona with minimal damage to current beauty ideology. From the 1990s onward, young men competing in the heterosexual marketplace, and thus concerned with their status as objects of female evaluation, began to engage in beauty work that would help them approximate the appearance of boys and men found in manga and anime (Miller 2006). No different than living men, Seimei divination books, posters, manga, and other imagery also conform to the desires of an imagined female consumer.

The science fiction writer Yumemakura Baku played a key role in encouraging this type of appropriation when he began publishing a series of novels with Seimei as the handsome hero in 1988. He describes Seimei as a slender and tall young man with a fine complexion. In interviews, Yumemakura admitted that he was targeting female fans of the bishōnen, or “beautiful young man,” when he set his pen to the page. The medieval folktales only described Seimei as an elder or as a child, so Yumemakura saw an opportunity to turn the established wizard into a cute dandy who would appeal to young women. In particular, Yumemakura wanted to entice female fans of the boys’ love genre by insinuating that there was a romantic relationship between Seimei and the handsome young court noble Minamoto no Hiromasa. Yumemakura later collaborated with manga artist Okano Reiko on a thirteen-volume series about Seimei that represents him as a gorgeous young man with a sculpted face (Okano and Yumemakura 1999–2005). In 2001, Okano and Yumemakura won the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for their efforts.

When contemporary popular culture producers like Yumemakura set out to create manga, anime, film, and television versions of Seimei, they often find that the beauty standards of long ago are quite different from viewer expectations today. Rather than try to represent Seimei as a typical Heian-era man with a chubby face and cheeks, most culture producers and fans meld some aspects of historic fashion with current hairstyles and body aesthetics. Although these representations reflect creative engagement with history, they also reassure consumers that their notions of beauty are natural instead of historically contingent. It is worth thinking about this selective appropriation of history, because these images are so powerful and have such a strong role in how people think about the past. Narratives about historic figures are often informed by the worldview of the present. Although representations of characters from history constitute a dance that invites us with dazzling imagery and will connect with themes we already know and love, it is risky. We might be learning more about the culture producer’s model of the world than about historic details of the figure being showcased.[2] An example from one of the many Seimei folktales is a good illustration of this process.

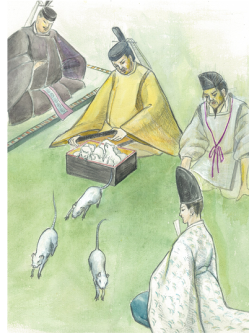

Painting at Seimei Jinja.

Two of the grand wizards of their time, Abe no Seimei and Ashiya Dōman are occasionally described in medieval folktales as rivals for the role of supreme onmyōji. They compete in battles to test their supernatural abilities. In one case, a challenge was arranged by the emperor, who presents them with a box and asks them to divine its contents. Dōman has bribed a servant to place fifteen tangerines inside and gives this as his answer, but Seimei uses magic to turn the fruit into rats and is thus able to win the contest after the lid is lifted and the rodents escape. In a collection of woodcuts and sketches published between 1814 and 1878, artist Katsushika Hokusai included one of this scene (reproduced in Fujimaki 2000, 119). In his illustration, Seimei and Dōman are crusty middle-aged sorcerers with facial hair. When this story has been appropriated in recent manga, however, the two wizards are transformed into beautiful young men. An example is found in A Seimei Oddity, where both men have large eyes, narrow faces, and long flowing hair (Kanpe and Misaka 2001). Another recent representation of this scene is found on the grounds of Seimei Jinja, a Shintō shrine in Kyoto dedicated to Seimei and built on the site of his home in 1007. After what has come to be known as the “Seimei boom” of the 1990s, so many fans visited the shrine that they were able to refurbish the buildings and precincts. They also added a series of newly commissioned paintings, which are placed on the outside walls of one of the buildings. These illustrate some of the more famous tales, including the wizard battle with Dōman. Drawn in a semimanga style, the scene of the rats emerging from the box presents Seimei as a young man with clear skin and a lovely profile. Seimei Jinja uses a variety of appropriated images and texts of the wizard in order to create interest in the now deified figure. Such appropriations help us see the ways that current ideology influences not only what gets appropriated, but also how those appropriated images and texts are modified, and why.

The Legend of Abe no Seimei (Mizuki 2013).

Similar to other shrines and temples, Seimei Jinja’s income is largely dependent on visitors purchasing amulets and other items from their kiosk. The avalanche of Seimei fans proved most welcome, and soon the shrine was doing brisk business in cellphone straps, cotton hand towels, notebooks, buttons, and other goods with Seimei-related imagery. In 2013, the shrine promoted a newly reissued manga booklet illustrated by Mizuki Shigeru (1922–2015), a popular folklore chronicler and manga artist. The original manga was part of a series from the Heian folktale collection Anthology of Tales from the Past (Mizuki 1991), which contains many Seimei stories. The publisher retitled one of the booklets in the series as a service for the shrine. The shrine in turn donated 10,000 copies to public junior high schools around the nation to help promote Classics Day (Koten no Hi). At the time of its release, Head Priest Yamaguchi Takuya praised the manga because it presents Seimei stories in modern language, which makes them more accessible (Seimei Jinja 2013). Yamaguchi said he hoped the beautifully drawn manga would help encourage junior high school students to learn about classical literature and would provide historical background to enrich future visits to the shrine.

Seimei is drawn in Mizuki’s trademark droopy-eye style as a chubby-faced elder, a stunning departure from the other imagery promoted by the shrine. At the start of the Seimei boom, the shrine focused on attracting young women enamored with bishōnen and boys’ love themes found in Seimei media. For example, they hung special large votive plaques signed by luminaries such as Yumemakura and the actors who starred in the films and television programs. In recent years, Seimei Jinja works to attract visitors in any manner possible. It has a hokey painted wooden board, called kaohame (face insert), depicting Seimei and a spirit helper with holes in it for people to put their heads through. They also lend out a huge cardboard Facebook frame prop with the name of the shrine on it. They host a jazzy Facebook page with regular updates of celebrity visitors to the shrine, videos, notices about annual shrine events, photographs of female shrine attendants holding cute new amulets and of cosplaying visitors, and a poster advertising a stamp rally, a type of scavenger hunt for fans of a popular anime series. The Mizuki manga is added to this mix perhaps to appeal to older visitors, and also to capitalize on the success of Mizuki’s hometown of Sakaiminato, where a museum and street dedicated to his manga characters draw many visitors.

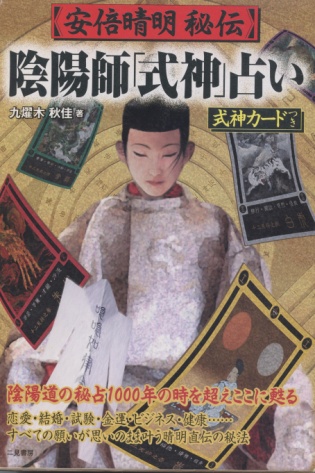

The Secrets of Abe no Seimei: Divination with the Wizard’s “Spirit Helpers” (Kuyōgi 2001).

Appropriations of Seimei have also spun out into the occult goods and information industry, where his image is used to index the magical and supernatural. For those who want to study how to become an accomplished wizard like Seimei, books offer precise instructions on the types of spells and enchantments he is said to have used. There are handsome boxed book sets with titles such as Abe no Seimei’s Secret Tricks: Writings on the Four Treasures and Tools of the Way of the Wizard for Spells and Incantations (Abe no Seimei higi: Onmyōdo jusengu shihō shinsho, Kuyōgi 2002) or The Secrets of Abe no Seimei: Divination With the Wizard’s “Spirit Helpers” (Abe no Seimei hiden: Onmyōji “shikigami” uranai, Kuyōgi 2001). These lucrative tomes contain directions for use as well as occult objects such as divination dice, paper effigies, cosmographic divination boards, and Taoist talisman slips (cf. Kuyōgi 2003; Taguchi 2002). Since the early 2000s, girls and women rule the divination industry, so the themes and images found in most divination goods and books are intended to appeal to them. Female aesthetics and tastes are evident in many new or hybrid fortune-telling types and services. Authors such as the prolific Kuyōgi Shūkei found that their books were most profitable if they featured images of a beautiful young Seimei and also included objects that girls and women could put together for their own magic play.

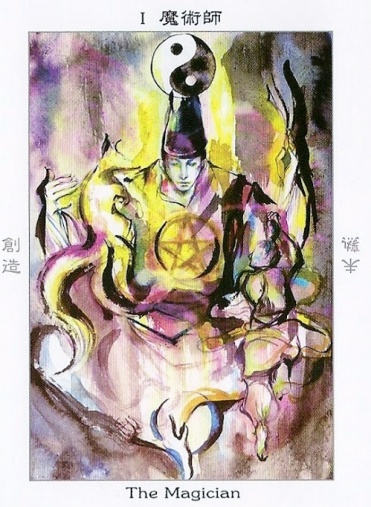

Tarot Card of The Magician (Itateyama 2012).

Stretching beyond appropriation of Seimei in divination books is his unique appearance as a figure in Japanese tarot cards. Although the tarot deck originated in Europe, there are now more than 1,500 unique ones created by Japanese artists. These new decks often domesticate the borrowed images of medieval European queens, knights, and pages by substituting figures from Japanese history or culture (Miller 2011). This is most apparent on the twenty-two cards that represent iconic themes or archetypes, such as the Sun, Temperance, the High Priestess, and the Magician. It is not surprising then that Seimei is sometimes used as a substitute for the Magician card (for example, see Itateyama 2012).

Appropriating cultural heritage for novel themes and appealing subjects is common in many media contexts and is certainly not unique to, or new in, Japan. The 1950s saw cinematic appropriations of samurai heroes, and more recently, the figure of the Edo-period (1603–1868) courtesan from the highest ranks of the pleasure district. For example, a story about a young maid named Tomeki who ascends the ranks of hierarchical sex workers in the Yoshiwara quarters became a successful manga and art house film (Anno 2001; Ninagawa 2007). Appropriations of Seimei are worth thinking about, not so that we might reveal anachronisms or errors but rather for what they tell us about the concerns and desires circulating in contemporary culture.

Charisma Wizard Dude (Taki 2002).

Interest in Seimei and his occult science is tied to the escalation in the feminized divination industry. Critics of girls and women who pursue divination characterize their activities as an irrational belief that detracts from their putative duties as productive baby incubators and workaholic citizens. One way to undermine these critics is to valorize magical practices from an esteemed period of history associated with a venerated historical person. By relocating occult pursuits to the glorious national past, consumers of Seimei deflect criticism while subversively encoding their own tastes and desires. Reworkings of Seimei bring increased attention to a figure buried in musty accounts and of little prior interest to postwar consumers. In addition, the homoerotic subtext of many Seimei products is evidence of the power of girls and women in the popular culture and media economy. Returning to the original folktales that set up Abe no Seimei and Ashiya Dōman as rivals, we now find new twists on their relationship. Instead of adversaries, they are paired in erotic love stories, naked and embracing in amateur comics such as Charisma Wizard Dude (Taki 2002). Girls and young women relish Seimei poaching activities because it affords them an opportunity to celebrate the things they love—bishōnen, boys’ love themes, and divination. Appropriation of a historic figure such as Seimei serves to reclaim him in ways that make sense and make him one’s own.

Notes

- Seimei joins other historic male figures who are subject to imaginative treatments in popular culture. Suter (2015) discusses iterations of the teenage leader of the Shimabara rebellion, Amakusa Shirō (1621–38). In some cases, Amakusa is paired in male-male relationships, something we also find with treatments of Seimei. Amakusa might also be cast as a cross-dressed figure, paralleled in some Seimei media. For example, at the end of the film Onmyōji 2 (Takita 2003), Seimei performs a dance dressed as a miko (female Shintō shrine attendant). ↑

- One example is Himiko (170–248), an ancient shaman ruler who has recently been reimagined in manga, film, computer games, and elsewhere (Miller 2014a). The uses of her image are symbolic of ongoing struggles in gender politics, and they often allow the media creator and consumer to place her in a known constellation of female slots that buttress existing gender stereotypes. ↑

References

Anno Moyoko. 2001. Sakuran. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Fiske, John. 1989. Understanding Popular Culture. Boston: Unwin-Hyman Publishers.

Fujimaki Kazuho. 2000. Abe no Seimei. Tokyo: Gakken.

Jenkins, Henry, III. 1988.“Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 5, no. 2: 85–107.

Hayami Yoku, and Koyanagi Junji. 2003. Gōsuto basutā Abe no Seimei [Ghost Buster Abe no Seimei]. Tokyo: Gakken.

Itateyama Misuzu. 2012. Wa tarotto [Tarot card of The Magician]. Tokyo: Azusa Shoin.

Kanpe Akira, and Misaka. 2001. Seimei kitan. Tokyo: Gakken.

Kuyōgi Shūkei. 2001. Abe no Seimei hiden: Onmyōji “shikigami” uranai [The Secrets of Abe no Seimei: Divination with the Wizard’s “Spirit Helpers”]. Tokyo: Futami Shobō.

Kuyōgi Shūkei. 2002. Abe no Seimei higi: Onmyōdo jusengu shihō shinsho. Tokyo: Futami Shobō.

Kuyōgi Shūkei. 2003. Abe no Seimei gokui onmyōdo, katatagae, yakuyoke jusen. Tokyo: Futami Shobō.

Mercer, Kobena. 1987. “Black Hair/Style Politics.” New Formations 3: 33–54.

Miller, Laura. 2006. Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Miller, Laura. 2008. “Extreme Makeover for a Heian-Era Wizard.” In Mechademia 3: Limits of the Human, edited by Frenchy Lunning, 30–45. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Miller, Laura. 2011. “Tantalizing Tarot and Cute Cartomancy in Japan.” Japanese Studies 31, no. 1: 73–91.

Miller, Laura. 2014a. “Rebranding Himiko, the Shaman Queen of Ancient History.” In Mechademia 9: Origins, edited by Frenchy Lunning, 179–98. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Miller, Laura. 2014b. “The Divination Arts in Girl Culture.” In Capturing Contemporary Japan: Differentiation and Uncertainty, edited by Satsuki Kawano, Glenda S. Roberts, and Susan Orpett Long, 334–58. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Mizuki Shigeru. 1991. Manga Nihon no koten 9: Konjaku monogatari-shū. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Shinsha.

Mizuki Shigeru. 2013. Abe no Seimei kōden [The Legend of Abe no Seimei]. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Shinsha.

Newton, Nell Jessup. 1997. “Memory and Misrepresentation: Representing Crazy Horse in Tribunal Court.” In Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation, edited by Bruce Ziff and Pratima V. Rao, 195–224. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ninagawa Mika, dir. 2007. Sakuran. Tokyo: Asmik Ace Entertainment.

Odagiri Masaaki, dir. 2001. Onmyōji [The yin-yang master]. NHK TV drama series. Aired April 3 to June 5, 2001.

Okano Reiko, and Yumemakura Baku. 1999–2005. Onmyōji. Tokyo: Hakusensha.

Rogers, Richard A. 2006. “From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation: Review and Reconceptualization of Cultural Appropriation.” Communication Theory 16: 474–503.

Seimei Jinja. 2013. “Abe no Seimei wo matsuru Seimei Jinja ga Mizuki Shigeru-shi saku konjaku monogatari wo kaita manga shōsasshi ‘Abe no Seimei kōden’ wo zenkoku no chūgakkō ni muryō de shintei,” August 9, 2013. https://www.atpress.ne.jp/news/37861.

Sugawa-Shimada, Akiko. 2015. “Rekijo, Pilgrimage and ‘Pop-Spiritualism’: Pop-Culture-Induced Heritage Tourism of/for Young Women.” Japan Forum 27, no. 1: 37–58.

Suter, Rebecca. 2015. Holy Ghosts: The Christian Century in Modern Japanese Fiction. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Taguchi Shindō. 2002. Abe no Seimei chokuban uranai. Tokyo: Futami Shobō.

Taki Ringa. 2002. Karisuma onmyōji kun [Charisma Wizard Dude]. Self-published manga.

Takita Yōjirō, dir. 2001. Onmyōji [The yin-yang master]. Pioneer (later renamed Geneon Entertainment) and Tōhō.

Takita Yōjirō, dir. 2003. Onmyōji 2 [The ying-yang master 2]. Geneon Entertainment and Tōhō.

Yamashita Tomohiko, dir. 2015. Onmyōji [The yin-yang master]. Special television drama movie. TV Asahi. Aired September 13, 2015.

Yumemakura Baku. 1988. Onmyōji. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū.

Ziff, Bruce, and Pratima V. Rao, eds. 1997. Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.