Ph.D. Candidate, Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Berkeley

Derived from the Latin term “limen,” meaning “threshold,” liminality refers to in-betweenness.[1] In the first decade of the twentieth century, anthropologist Arnold van Gennep (2004) formulated the notion of liminality in delineating three stages of “rites of passage,” or rites accompanying socially transformative events such as childbirth or marriage: separation from the community, transition across a culturally significant threshold, and reincorporation into the community. Half a century later, anthropologist Victor Turner recalibrated van Gennep’s framework in a study of the initiation rites accompanying “boys becoming men” among the Ndembu of Zambia (Turner 1979a). At the time, anthropological theory tended toward Levi-Straussian structuralism, which conceptualized cultures as organisms consisting of static structures or “finished texts” (Thomassen 2009, 13), such as myths and kinship networks, that serve particular and necessary social functions. Turner was seeking an alternative approach that would reopen these static structures to dynamic and unforeseen developments. Foreshadowing his later turn to performative “social dramas” (Turner 1988), Turner reframed the liminal stage of van Gennep’s transitional rites as a series of contingent events that not only reaffirm but also generatively influence a society’s broader social structure, or patterned arrangements of social roles and statuses informed by political norms and sanctions (Turner 1974a, 201; see also Szakolczai 2009, 142).

For Turner, liminal rites mobilize ritual symbols that contribute to the general “Undoing, dissolution, [and] decomposition” of the givens of the preliminal cultural order (1979a, 237; see also 1974a, 55). One consequence of this ritual destructuring is to displace initiates from their previous structural positions in social life and into “betwixt-and-between” interstructural positions, from which they subsequently proceed to new structural positions following rites of reincorporation (Turner 1979a). It is precisely the state of being betwixt-and-between, as well as the modes of sociality it affords, that have been Turner’s lasting contributions to later scholarship. These modes of sociality are twofold. On the one hand, liminal rites of passage occur prior to rites of reincorporation that confirm the integrity of the nonliminal social structure (ibid., 235). As Turner sees it, betwixt-and-between initiates absorb new forms of knowledge concerning the customs, beliefs, and values of the wider social group through ritualized engagements with various symbolic implements. Acquiring this knowledge entails an ontological change in the initiate such that, upon reincorporation into the broader social group, s/he occupies a new social role or status. Here, then, liminality ultimately serves a conservative function by paving the way for the communal reintegration of socially transformed initiates and, in that way, the perpetuation of the community’s social structure.

On the other hand, liminality exhibits a kind of “subjunctive mood” as a state “full of potency and potentiality” (Turner 1979b, 95). According to Turner, rites of passage often include moments of “antistructure,” involving, for example, the ritual degradation of otherwise respected community members, playing with bizarre or grotesque symbolic objects, and general antinomian behavior (Turner 1969, chap. 3; 1974a, 256–57; 1977, 38; Turner 1979b, 95–96; see also Bakhtin 1968). By upending the givens of social life in this way, antistructure can both spark reflexive consideration among initiates of what had been culturally given in preliminal society, and further reconstitute social relations among initiates into what Turner calls “communitas,” perhaps best understood as an uninhibited togetherness.[2] For these reasons, while antistructure is often restrained through the ritual incorporation of symbolic checks such as taboos, the liminality of rites of passage can reshuffle social relations in ways that have lasting consequences for the postliminal social order. Liminality, then, has the potential to animate the processual transformation of the social structure itself (Turner 1969, 1974a, 1977, 1979a, 1979b; see also Sahlins 1981).

In his later work, Turner introduced a historical shift between “the tribal-liminal and the industrial-liminoid” (1977, 47). As defined by Turner, the liminoid refers to diverse “genres of industrial leisure” (ibid., 71), which might include painting, rock music, and massive multiplayer online roleplaying games. Liminoid phenomena resemble liminal rites of passage insofar as they distill the factors of culture into manifold symbols, bear the antistructural potential to rearrange social relations, and, even more so than their predecessors, offer metasocial commentaries on everyday existence (Turner 1974c, 1979b). Yet whereas liminality characterizes obligatory, regular rites of passage that govern transitions between relatively static social roles in small-scale communities, the liminoid characterizes intermittent and voluntary “genres” of phenomena that involve passage between fluid social spaces and times of leisure in the context of urban and secular industrial capitalism. In passing to the liminoid, the liminal grows personalized and pluralistic, penetrates quotidian spaces such as theaters and stadiums, and destructures cultural life with relative freedom from collective symbolic structure and restraint (Turner 1974b, 1977, 1979b).

While Turner has been critiqued for invoking a consensual and idealistic model of social life that effaces conflicts of power undergirding liminal scenarios (Weber 1995), scholars have adjusted and deployed his paradigm in diverse inquiries that cut across academic disciplines. Whether in the form of liminal “plural reflexivity” in feminist literary studies (Babcock 1990), “double liminality” in investigations of international labor migration (Aguilar Jr. 1999), the liminal as a transformative catalyst in organizational studies (Howard-Grenville et. al. 2011), or the “liminal anxiety” of genre painting in art historiography (Ledbury 2007), liminality has provided a powerful analytic for examining in-betweenness in a variety of contexts. It has been productive in media studies as well. For example, Michael F. Leruth (2004) invokes Turner in analyzing the capacity of artist Fred Forest’s multimedia and web-based performances to facilitate a liminal intermixing of otherwise unconnected viewer-participants and, in so doing, to foster interpersonal engagement that is both reflexive and critical (recall “communitas”).

In the context of contemporary Japan, political scientist Susan J. Pharr (1996) characterizes mass media as a liminal trickster that can both buttress and spur critique of political and corporate institutions (recall “structure” and “antistructure”). Beyond the news, liminality is also useful for the study of Japanese media and popular culture. When considering the media and material culture associated with otaku, for example, liminality can shed light on the destructuring of boundaries between producers and consumers (Azuma 2009), merchandizing characters in media mixes (Steinberg 2009), and bringing together the “two-dimensional” world of manga and anime with the “three-dimensional” world of humans, as is particularly visible in Akihabara, a neighborhood in Tokyo’s Chiyoda Ward (Morikawa 2012).

The case of Mikoshī, the character-mascot of Kanda Myōjin that was created on the 400th anniversary of the shrine’s establishment in its current location in Chiyoda Ward, demonstrates liminality’s potential utility in analyzing the betwixt-and-between in Japanese media and popular culture. Described as a “child of Edo” (Edokko), Tokyo’s premodern name, Mikoshī’s design and ritual function can be productively understood in terms of the liminal and liminoid. Judging from the character’s name, ornamentation, and shape, Mikoshī is patterned after mikoshi, or portable sacred shrines, which are employed in the animistic religion of Shinto. Theoretically, mikoshi help foster a liminal spacetime that renews social and sacred bonds among deities and worshippers. They do so by transporting deities, which are usually housed at a shrine, around parishioner districts (Ashkenazi 1993). Kanda Myōjin’s biennial festival includes two events involving mikoshi: an “entering the shrine” (miyairi) ritual, in which dozens of mikoshi produced by parishioner districts carry the deities from the shrine back to their respective neighborhoods, and large processions of the shrine’s mikoshi alongside festival floats and performers, which are known as “auxiliary parades” (tsukematsuri).[3] In the 2015 procession, the shrine’s mikoshi traversed a threshold—that is, the shrine’s gate—subsequent to the rites of separation (the hatsurensai, or “departure ceremony”) and prior to the rites of reincorporation (the chakurensai, or “arrival ceremony”).[4] They were then joined by both auxiliary parades and Mikoshī. From this, one could argue that Mikoshī went on procession with the shrine’s mikoshi as an additional ritual implement.

The case of Mikoshī, the character-mascot of Kanda Myōjin that was created on the 400th anniversary of the shrine’s establishment in its current location in Chiyoda Ward, demonstrates liminality’s potential utility in analyzing the betwixt-and-between in Japanese media and popular culture. Described as a “child of Edo” (Edokko), Tokyo’s premodern name, Mikoshī’s design and ritual function can be productively understood in terms of the liminal and liminoid. Judging from the character’s name, ornamentation, and shape, Mikoshī is patterned after mikoshi, or portable sacred shrines, which are employed in the animistic religion of Shinto. Theoretically, mikoshi help foster a liminal spacetime that renews social and sacred bonds among deities and worshippers. They do so by transporting deities, which are usually housed at a shrine, around parishioner districts (Ashkenazi 1993). Kanda Myōjin’s biennial festival includes two events involving mikoshi: an “entering the shrine” (miyairi) ritual, in which dozens of mikoshi produced by parishioner districts carry the deities from the shrine back to their respective neighborhoods, and large processions of the shrine’s mikoshi alongside festival floats and performers, which are known as “auxiliary parades” (tsukematsuri).[3] In the 2015 procession, the shrine’s mikoshi traversed a threshold—that is, the shrine’s gate—subsequent to the rites of separation (the hatsurensai, or “departure ceremony”) and prior to the rites of reincorporation (the chakurensai, or “arrival ceremony”).[4] They were then joined by both auxiliary parades and Mikoshī. From this, one could argue that Mikoshī went on procession with the shrine’s mikoshi as an additional ritual implement.

Yet, although associated with deities and mikoshi, Mikoshī is neither. It is, rather, a characterization of mikoshi. Indeed, it is a betwixt-and-between figure whose design splices a traditional ritual implement that dates to at least the eighth century (Weinstein 1983) with the contemporary trend of cuddly character advertising (Alt and Yoda 2007). In this respect, it fuses ritual with the media and material culture of Akihabara, which numbers among Kanda Myōjin’s parishioner districts. A center for marketing otaku as branded pop culture (Galbraith 2010) as well as stores specializing in manga and anime character merchandise, Akihabara supplies the popular and commercial context for Mikoshī’s appearance, because financial and demographic pressures have made otaku patrons crucial to Kanda Myōjin in recent years.[5] Participation in and patronage of shrine functions is no longer obligatory,[6] and as such, commercial revenue has become indispensable for the shrine, as it has for other contemporary religious institutions. Moreover, Chiyoda Ward’s “donut-style” depopulation (Matsudaira 1994), where fewer people live in the area and more commute in for work and play, has resulted in a lack of manpower to transport some of the neighborhood mikoshi during the festival. For this reason, a number of parishioner districts solicit volunteers from among nonparishioners to transport their mikoshi (see Akino 2014, 2015, 2016). In these patently liminoid developments, “outsiders,” including nonparishioners and enthusiasts of otaku culture, buoy a noncompulsory festival still tied to sacred rituals (Turner 1979b, 116).

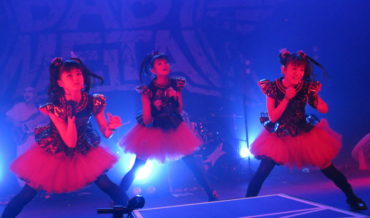

With limited finances and personnel, the shrine and its parishioner districts invigorate the festival and other events through adroit adaptations to popular taste, which result in ritual implements breaching the liminoid by incorporating pop cultural elements. For example, Kanda Myōjin has joined forces with students from the Tokyo University of the Arts and members of the Association for the Study of Cultural Resources to reintroduce folktale-themed auxiliary parades, which were central to the shrine’s mikoshi processions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but which now feature soft and exaggerated designs reminiscent of the aesthetics of manga and anime.[7] In addition, in 2009, the Akihabara Information Center (Akihabara annaijo) and some 100 stores and companies in Akihabara teamed up to produce the “Akiba mikoshi,”[8] perhaps a playful take on the neighborhood mikoshi. This “mikoshi” did not parade during the festival but was brought to the shrine precincts on a separate occasion.[9] The object exhibits a powerful otaku appeal, being outfitted with an antenna, red and blue lights, a solar panel, and games and manga. It was, furthermore, shouldered by individuals in maid uniforms, which links the mikoshi with Akihabara’s popular maid cafés.[10] To the extent that the procession’s auxiliary parades and the Akiba mikoshi operate as implements engendering novel social connections among parishioners and nonparishioners, they help to generate liminal spacetime, but insofar as they draw on secular leisure genres associated with otaku consumer culture and the aesthetics of otaku-related media, they are distinctly liminoid.

Similarly, the movement from the neighborhood mikoshi to Akihabara’s otaku-friendly mikoshi, as well as the characterization of mikoshi as Mikoshī, traces an arc from the liminal to the liminoid. A child of Edo—the name for Tokyo prior to 1868—Mikoshī embodies an amalgamation of preindustrial design and ritual function with the aesthetic and consumerist beat of character culture. That Mikoshī’s designer is none other than Esaka Masami, an artist best known for his work on the anime series Bikkuriman (aired 1987-89), speaks to this connection. Other shrine events have reinforced this link as well. For instance, the shrine’s Facebook account documents a “water-sprinkling” (uchimizu) ritual held at the shrine in August 2016, where Mikoshī stands beside Hello Kitty, Sanrio’s massively popular multimedia character, and young women in maid costumes. In this way, by virtue of associations with the Hello Kitty character and the general character-type “maid,” as well as Esaka’s adorable design, Mikoshī weaves together a ritual implement and the aesthetics of otaku and consumer culture.

Yet the betwixt-and-between Mikoshī not only reconciles a ritual implement with character advertising but also reconciles the physical space of the former with the multidimensional space of the latter. During the shrine mikoshi’s procession in 2015, Mikoshī walked Tokyo’s streets as a “three-dimensional” entity, that is, a person wearing a Mikoshī costume. In most media, however, it is a “two-dimensional” entity. Drawn with glinting eyes and a perky posture, Mikoshī stands almost as an exclamation point at the edge of the title atop Kanda Myōjin’s official homepage for the festival: “Fiscal year 2017, Kanda festival [picture of Mikoshī].”[11] By migrating between the screen and the streets, Mikoshī forms a liminoid bridge between the cyberspace and urban space of the festival. This bridging effect was further enhanced in 2015 by a live broadcast of Mikoshī and the rest of the procession on Kandamatsuri.ch,[12] and by Mikoshī’s presence in the shrine’s activities on social media networks such as Facebook and Twitter. Moreover, the same image of Mikoshī that decorates the festival’s website has appeared as both a physical signboard on Kanda Myōjin’s grounds as well as a mascot-logo printed on boxes of Japanese-style sweets created by the confectionary Bunsendō and sold at the shrine. In these ways, Mikoshī not only shifts between ritual implement and character-mascot but also achieves an ambiguous multidimensionality that overrides the division between the two- and three-dimensional.

Yet the betwixt-and-between Mikoshī not only reconciles a ritual implement with character advertising but also reconciles the physical space of the former with the multidimensional space of the latter. During the shrine mikoshi’s procession in 2015, Mikoshī walked Tokyo’s streets as a “three-dimensional” entity, that is, a person wearing a Mikoshī costume. In most media, however, it is a “two-dimensional” entity. Drawn with glinting eyes and a perky posture, Mikoshī stands almost as an exclamation point at the edge of the title atop Kanda Myōjin’s official homepage for the festival: “Fiscal year 2017, Kanda festival [picture of Mikoshī].”[11] By migrating between the screen and the streets, Mikoshī forms a liminoid bridge between the cyberspace and urban space of the festival. This bridging effect was further enhanced in 2015 by a live broadcast of Mikoshī and the rest of the procession on Kandamatsuri.ch,[12] and by Mikoshī’s presence in the shrine’s activities on social media networks such as Facebook and Twitter. Moreover, the same image of Mikoshī that decorates the festival’s website has appeared as both a physical signboard on Kanda Myōjin’s grounds as well as a mascot-logo printed on boxes of Japanese-style sweets created by the confectionary Bunsendō and sold at the shrine. In these ways, Mikoshī not only shifts between ritual implement and character-mascot but also achieves an ambiguous multidimensionality that overrides the division between the two- and three-dimensional.

Insofar as Mikoshī operates as a physical and virtual implement in the festival’s procession, we may ask to what extent it fosters the thick sociality (“communitas”) that Turner ascribed to liminal spacetime. Ethnographic fieldwork would be necessary to draw any firm conclusions, but one salient aspect of the contemporary festival points to Mikoshī’s capacity to bring together festival participants, patrons, and spectators. Mikoshī is only one piece of the broader revitalization of the shrine mikoshi’s procession in recent years, including the reintroduction of folktale-themed auxiliary parades into the festival. In a personal interview, one priest at Kanda Myōjin emphasized that these parades hold the potential to spread awareness of traditional legends perhaps unknown to young people that have grown up on Disney.[13] Just as the auxiliary parades might afford new social relations grounded in cultural narratives renovated with a popular cultural aesthetic, so too might Mikoshī mediate between the cultures of festival performance and character advertising to generate social bonds among parishioners in a manner adapted to the exigencies of contemporary Japan.

Insofar as Mikoshī operates as a physical and virtual implement in the festival’s procession, we may ask to what extent it fosters the thick sociality (“communitas”) that Turner ascribed to liminal spacetime. Ethnographic fieldwork would be necessary to draw any firm conclusions, but one salient aspect of the contemporary festival points to Mikoshī’s capacity to bring together festival participants, patrons, and spectators. Mikoshī is only one piece of the broader revitalization of the shrine mikoshi’s procession in recent years, including the reintroduction of folktale-themed auxiliary parades into the festival. In a personal interview, one priest at Kanda Myōjin emphasized that these parades hold the potential to spread awareness of traditional legends perhaps unknown to young people that have grown up on Disney.[13] Just as the auxiliary parades might afford new social relations grounded in cultural narratives renovated with a popular cultural aesthetic, so too might Mikoshī mediate between the cultures of festival performance and character advertising to generate social bonds among parishioners in a manner adapted to the exigencies of contemporary Japan.

While Mikoshī exemplifies the analytical power of liminality as a theoretical framework for studying media and popular culture, the potential of liminality extends to a range of phenomena in Japan today. To begin with, Kanda Myōjin is not the only religious institution leveraging the pull of otaku culture to attract young people (Tanaka 2010). Furthermore, as media scholar Tanimura Kaname has shown, shrines and associated market districts outside Tokyo have begun to capitalize on the popularity of both “anime pilgrimages” and character advertising, of the type seen in Akihabara, to entice patrons (Tanimura 2012).[14] How might liminality help us understand this sort of “contents tourism”? Indeed, how might liminality be applied to discussions of the crossovers between the two- and three-dimensional in otaku culture more generally? As scholars explore these and other questions, liminality will continue to offer a flexible analytic for illuminating various aspects of Japanese media and popular culture.

Notes

- On liminality’s intellectual history, see Thomassen (2009). ↑

- Or, as Turner has it: “Communitas is a direct, immediate confrontation or <<encounter>> between free, equal, levelled, and total human beings, no longer segmentalized into structurally defined roles [. . .] It means freedom, too, from class or caste affiliation, or family and lineage membership” (1974c, 307). ↑

- For the purposes of this essay, I do not distinguish between the shrine’s mikoshi and hōren. During the festival, each of the shrine’s three mikoshi is invested with one of the three deities housed at Kanda Myōjin. Each neighborhood mikoshi is invested with all three deities. ↑

- Due to bad weather, Mikoshī did not parade in 2017, but it did appear at a Yomiuri Giants baseball game in Tokyo Dome on May 4, 2017 alongside the Giants’ mascot. ↑

- The shrine is the destination of “anime pilgrimages” associated with programs like Love Live! (aired 2013–14) and Etotama (aired in 2015). It has further incorporated a float themed around Sgt. Frog (aired 2004–11) and collaborated with the media production company Xarts Japan in 2015 and 2017 to create limited-time products featuring characters from Love Live! and Sword Art Online (aired 2012, 2014); see “Anime to korabo: Wakai nekki, Kanda matsuri,” Sankei shinbun, May 10, 2015. Collaborative goods, posters, and flags printed with anime characters continue to enliven the precincts after the festival has concluded. ↑

- Though it was obligatory centuries ago (Kishikawa 2012, 11). ↑

- These auxiliary parades were, to a certain extent, already liminoid in the Edo period due to their propensity to draw upon popular cultural trends and exhibit exaggerated designs. Perhaps the most prominent of the recently reintroduced auxiliary parades is a float of a demon’s head thematizing the legend of Shuten Dōji. ↑

- “Kanda myōjin de no katsudō”: http://akiba-guide.com/kandamyoujin.html (accessed May 23, 2017). ↑

- Because no god was invested in the mikoshi, this was not a miyairi ritual. ↑

- “Keroro gunsō, Kanda matsuri ni: Akiba o genki ni shitai de arimasu, 9-ka no tsukematsuri, kodomo-tachi hiki-mawashi,” Tōkyō shinbun, May 6, 2009; “Mēdo sugata de ‘seiyā,’ ‘Akiba MIKOSHI’ debyū,” Tōkyō shinbun, April 27, 2009. ↑

- “Heisei 29 nendo: Kanda matsuri”: http://www.kandamyoujin.or.jp/kandamatsuri/ (accessed May 11, 2017). ↑

- A picture of Mikoshī also appeared as a logo in the upper-right corner of the video feed in 2017. On internet-mediated festivals, see Tanimura 2008. ↑

- Personal interview with the author (July 7, 2015). ↑

- See Imai 2009, 2010; Andrews 2014; Sugawa-Shimada 2015. ↑

References

Aguilar, Filomeno V., Jr. 1999. “Ritual Passage and the Reconstruction of Selfhood in International Labour Migration.” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 14, no. 1: 98–139.

Akino, Jun’ichi. 2014. “‘Ganso onna mikoshi’ no hensen ni miru chiiki shakai no hen’yō to Kanda matsuri.” Kokugakuin daigaku daigakuin kiyō (bungaku kenkyūka) 45: 111–31.

Akino, Jun’ichi. 2015. “Toshi matsuri no keinen-teki henka: Sengo no chiiki shakai no hen’yō to Kanda matsuri gojūnen no seisui.” Kokugakuin zasshi 116, no. 11: 30–54.

Akino, Jun’ichi. 2016. “‘Ganso onna mikoshi’ ni miru sankasha no jittai to Kanda matsuri: ‘Dentō-gata’ toshi shukusai no naka no ‘gōshū-gata.’” Kokugakuin daigaku kenkyū kaihatsu suishin sentā kenkyū kiyō 10: 173–99.

Alt, Matt, and Hiroko Yoda. 2007. Hello, Please! Very Helpful Super Kawaii Characters from Japan. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Andrews, Dale K. 2014. “Genesis at the Shrine: The Votive Art of an Anime Pilgrimage.” In Mechademia 9, edited by Frenchy Lunning, 217–33. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ashkenazi, Michael. 1993. Matsuri: Festivals of a Japanese Town. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Azuma, Hiroki. 2009. Otaku: Japanese Database Animals. Translated by Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Babcock, Barbara A. 1990. “Mud, Mirrors, and Making Up: Liminality and Reflexivity in Between the Acts.” In Victor Turner and the Construction of Cultural Criticism: Between Literature and Anthropology, edited by Kathleen M. Ashley, 86–116. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1968. Rabelais and His World. Translated by Helene Iswolsky. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Galbraith, Patrick W. 2010. “Akihabara: Conditioning a Public ‘Otaku’ Image.” In Mechademia 5, edited by Frenchy Lunning, 210–30. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Howard-Grenville, Jennifer, et. al. 2011. “Liminality as Cultural Process for Cultural Change.” Organization Science 22, no. 2: 522–39.

Imai, Nobuharu. 2009. “Anime ‘seichi junrei’ jissensha no kōdō ni miru dentō-teki junrei to kankō katsudō no kakyō kanōsei: Saitama-ken Washinomiya jinja hōnō ema bunseki o chūshin ni.” In Vol. 1 of CATS sōsho, edited by Hokkaidō daigaku kankōgaku kōtō kenkyū sentā bunka shigen manejimento kenkyū chīmu, 87–111. Hokkaido: Hokkaidō daigaku kankōgaku kōtō kenkyū sentā.

Imai, Nobuharu. 2010. “The Momentary and Placeless Community: Constructing a New Community with regards to Otaku Culture.” Inter Faculty 1 (2010), University of Tsukuba. https://journal.hass.tsukuba.ac.jp/interfaculty/article/view/9/11.

Kishikawa, Masanori. 2012. “Edo no jinja sairei: Sono katachi to shikkō jōkyō.” Kokugakuin daigaku kenkyū kaihatsu suishin kikō kiyō 4: 1–36.

Ledbury, Mark. 2007. “Greuze in Limbo: Being ‘Betwixt and Between.’” Studies in the History of Art 72: 178–99.

Leruth, Michael F. 2004. “From Aesthetics to Liminality: The Web Art of Fred Forest.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 37, no. 2: 79-106.

Matsudaira, Makoto. 1994. Gendai Nippon matsuri-kō: Toshi matsuri no dentō o tsukuru hitobito. Tokyo: Shōgakukan.

Morikawa, Ka’ichirō. 2012. “Otaku and the City: The Rebirth of Akihabara.” In Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World, edited by Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe, and Izumi Tsuji, 133–57. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pharr, Susan J. 1996. “Media as Trickster in Japan: A Comparative Perspective.” In Media and Politics in Japan, edited by Susan J. Pharr and Ellis S. Krauss, 19–43. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Sahlins, Marshall. 1981. Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities: Structure in the Early History of the Sandwich Islands Kingdom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Steinberg, Marc. 2009. “Anytime, Anywhere: Tetsuwan Atomu Stickers and the Emergence of Character Merchandizing.” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 2–3: 113–38.

Sugawa-Shimada, Akiko. 2015. “Rekijo, Pilgrimage and ‘Pop-Spiritualism’: Pop-Culture-Induced Heritage Tourism of/for Young Women.” Japan Forum 27, no. 1: 37–58.

Szakolczai, Arpad. 2009. “Liminality and Experience: Structuring Transitory Situations and Transformative Events.” International Political Anthropology 2, no. 1: 141–72.

Tanaka, Miya. 2010. “Temple Turns to ‘Anime’ to Lure the Young.” The Japan Times, December 25, 2010. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2010/12/25/national/temple-turns-to-anime-to-lure-the-young/#.VxSjWhMrLGJ.

Tanimura, Kaname. 2008. “Jiko mokuteki-ka suru intānetto no ‘matsuri’: ‘Yoshinoya matsuri’ to ‘“Hare hare yukai” dansu matsuri’ no hikaku kara.” Kwansei gakuin daigaku shakai gakubu kiyō 104: 139–52.

Tanimura, Kaname. 2012. “‘Anime seichi’ ni okeru shumi no hyōshutsu: ‘Shuto’ to ‘anime seichi’ no hikaku kara.” In Vol. 7 of CATS sōsho, edited by Yamamura Takayoshi and Okamoto Takeshi, 105–20. Hokkaido: Hokkaidō daigaku kankōgaku kōtō kenkyū sentā.

Thomassen, Bjørn. 2009. “The Uses and Meanings of Liminality.” International Political Anthropology 2, no. 1: 5–27.

Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Cornell University Press.

Turner, Victor. 1974a. Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Turner, Victor. 1974b. “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology.” In The Anthropological Study of Human Play, edited by Edward Norbeck, 53–92. Houston, TX: William Marsh Rice University.

Turner, Victor. 1974c. “Pilgrimage and Communitas.” Studia Missionalia 23: 305–27.

Turner, Victor. 1977. “Variations on a Theme of Liminality.” In Secular Ritual, edited by Sally F. Moore and Barbara G. Myerhoff, 36–52. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Turner, Victor. 1979a. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage.” In Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach, edited by William A. Lessa and Evon Z. Vogt, 234–43. 4th ed. New York: Harper and Row.

Turner, Victor. 1979b. “Frame, Flow and Reflection: Ritual Drama as Public Liminality.” In Process, Performance and Pilgrimage: A Study in Comparative Symbology, 94–120. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Turner, Victor. 1988. “The Anthropology of Performance.” In The Anthropology of Performance, 72–98. New York: PAJ Publications.

van Gennep, Arnold. 2004. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee. London: Routledge.

Weber, Donald. 1995. “From Limen to Border: A Meditation on the Legacy of Victor Turner for American Cultural Studies.” American Quarterly 47, no. 3: 525–36.

Weinstein, Stanley. 1983. “Mikoshi.” In Vol. 5 of Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, 172. Tokyo: Kodansha, Ltd.