Senior Lecturer, School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield

Genre, from the French word for “kind,” is both a keyword and foundational concept in the study of media. Genre seems relatively straightforward: Films, television shows, online material, and other media are assigned a genre when they are discussed as a particular “kind” that markets to specific audiences. When we use “genre” as a concept in the study of media, however, it can cause problems. Industrial and audience genre expectations, critical assessment of a film’s contribution to a corpus, and ideas about what constitute normative components of a genre are often in conflict.

In his foundational work, Stephen Neale argues that, “genres are not systems, they are processes of systematization” (1980, 51). “Genre” is not only “romance,” “horror,” “sci-fi,” and so on, but also the process of assigning a text such a label. But how do we decide which label to assign? Many media texts are a fusion of several narrative or stylistic components that we understand as belonging to a particular “kind.” Neale elaborates his description of genre to encompass three specific areas: industrial and audience expectation, contribution to a generic corpus, and the rules or norms by which a genre film must abide (1990, 56). For Neale, “genres are instances of repetition and difference” (1980, 51). But how much repetition, and of what kind, qualifies a text as a certain genre? Conversely, what degree of difference would disqualify a text from a genre classification?

Some scholars suggest categorizing genre based on intentionalities in the creation or marketing of a film. “Intentionalities” encompass the artistic aims of the directors, actors, cinematographers, and others, as well as the commercial goals of producers and marketing teams. However, intentionality is hard to interpret with any certainty. Audience expectation complicates questions of intent, because audiences expect certain qualities within a specific genre (Neale 1990, 46). For example, audiences at a romance film will expect a romance to be central to the narrative. The text’s “regimes of verisimilitude” (ibid., 48), or what is considered possible within the world of the film, are contingent on an audience’s understanding of its genre. The kinds of narrative events, characterizations, visual imagery, and tone that audiences accept as plausible are dictated by preexisting expectations of the genre’s norms and conditions. Genre therefore shapes a film’s “narrative image” (ibid., 49), and we must also be aware of the “industrial/journalistic” use of “genre” (Altman 1989, 13) in shaping a film’s reputation.

Genre as a process can be fluid to the point of confusion. Robert Stam questions whether genres are really “out there” in the world or simply the construction of analysts (2000, 14), while David Bordwell identifies as common to genre the grouping of texts by diverse criteria, including period, country, director, star, producer, writer, studio, technical process, “cycle,” series, style, structure, ideology, venue, purpose, audience, or subject (1989, 148). Stam observes that while some genres are defined by narrative content, others are borrowed from literature (comedy or melodrama) or from other media (for example, the musical), or defined by the performer, budget, artistic status, or viewer orientation (2000, 14). In “Rethinking Genre,” Christine Gledhill rejects the idea of “rigid rules of inclusion and exclusion” (2007, 60), arguing that genres “are not discrete systems, consisting of a fixed number of listable items” (ibid.).

Meanwhile, Andrew Tudor notes that “the meaning and uses” of the term genre “vary considerably,” arguing that “it is very difficult to identify even a tenuous school of thought on the subject” and cautioning against “extreme genre imperialism” (1983, 3). This intervention is crucially related to the practice of relying on preexisting genre categories to analyze films, rather than generating the genre classification terminology from analysis (Neale 1990, 50; Cohen 1986, 207). How can we establish whether a text truly fits a genre category when we have created that category before analyzing the text?

Scholars have attempted to improve the study of genre by making certain clarifications. Altman argues for the separation of genre theory and genre history as areas of study (1999, 84), while John Swales suggests describing genres in terms of “family resemblances” among texts (1990, 49). Meanwhile, Alan Williams states simply that “we need to get out of the United States” (1984, 124). Taking the Japanese yakuza genre and the career of Fuji Junko as case study, we can see how industrial and audience genre expectations, critical assessment of a film’s contribution to the corpus of yakuza film, and ideas about what constitute normative components of the yakuza film, both conflict and blend in popular texts.

The history of Japanese yakuza film illustrates the key issues in classifying films by genre. While the yakuza genre is now one of Japanese cinema’s best known, its development as a stand-alone genre is relatively recent. Early films, such as Chūji’s Travel Diary (Chūji tabi nikki; Ito Daisuke, 1927–28, in three parts) told of the wandering gamblers who would become contemporary yakuza, but such films were not widely recognized as a genre until the postwar era. As the modern yakuza legend is based on the subcultural identity that grew among wandering gamblers (bakuto) and peddlers (tekiya) in the Edo period (1603–1868), a historic definition of the yakuza genre would incorporate little more than itinerant protagonists, gambling, swordsmanship, and perhaps the performance of formal introductions as set pieces.

However, much extant scholarship on the yakuza genre begins from a point past the issue of classification and does not question key assumptions in the process of grouping these films together. Since Paul Schrader (1974, 10) argued that the first “authentic” yakuza film dates from 1964, with the release of Gambler (Bakuto; Ozawa Shigehiro), much of the literature on yakuza film has been restricted to this era and follows Schrader’s “top down” model, focusing on particular studios, directors, and actors (Desjardins 2005; Schilling 2003; Gerow 2005). A composite definition of the yakuza genre drawn from this body of scholarship would appear to be films starring select male actors (for example, Takakura Ken), directed by certain male auteurs (such as Kato Tai or Ishii Teruo), including scenes of fighting and violence, and dealing with a lone hero struggling against a corrupt social system, often in contemporary urban centers or prisons.

Narrow definitions of what constitutes a yakuza film are a problem because the codes and rituals of contemporary yakuza film draw from a wide range of historical media and myth. The vertical hierarchies of the yakuza “family” stem from the Meiji reorganization of groups of gamblers into structured, quasi-legal bodies, while the formal introductions performed by yakuza characters are borrowed from the wandering peddlers, who performed similar introductions to gain access to lodgings. The modern yakuza image also has antecedents in the legends of “chivalrous commoners” (kyōkaku), who protected their local communities. These figures are frequently referenced in yakuza film titles such as the series An Account of the Chivalrous Commoners of Japan (Nihon kyōkaku den; 1964–71). The yakuza genre drew from popular myth as well as history; the Chūji character of Chūji’s Travel Diary is based on the quasi-mythical gambler hero Kunisada Chūji (1810–50), who epitomizes many of the tropes still central to yakuza film, including ethically based resistance to authority, the lone hero, and violent set pieces.

The diversity of yakuza-related media resists simple genre classification. Yakuza film works across genres; the postwar hooligan (gurentai) style was modeled on American gangster narratives, while Edo-period yakuza films incorporate elements of historical drama (jidaigeki), and even romance, in subplots centered around love interests. In the late 1950s, Misora Hibari popularized the yakuza musical, while stars such as Takakura Ken, Fuji Junko, and Kaji Meiko recorded enka-style (“traditional” Japanese) hits of the title songs of their 1960s and 1970s yakuza films. Even the avant-garde directors, who comprised the studios’ “nouvelle vague” (nuberu bāgu), incorporated yakuza themes, such as Imamura Shōhei’s Pigs and Battleships (Buta to gunkan; 1964). Subgenres in 1970s cinema also blurred the lines between yakuza genres and pornographic genres (Higuchi 2009).

The association of the yakuza genre with masculine protagonists and male audiences, particularly in English language scholarship, tends to overlook the large number of films featuring yakuza narratives or themes and starring female protagonists. However, criticism published in popular film magazines of the period, such as Kinema Junpō and Eiga Geijutsu, shows that a large number of popular films featured female yakuza or gambler protagonists (Coates 2017). While the first yakuza heroine to be seriously studied was Misora Hibari (MacDonald 1992, 181), Yomota Inuhiko and Washitani Hana (2009) include the female yakuza heroine in a broader study on female representation in action film, and Pinky Violence: Tōei’s Bad Girl Films (Tōei pinki baiorensu roman arubamu; 1999) intersperses directors’ interviews with picture galleries visually illustrating the development of the yakuza heroine, from Fuji Junko to Ike Reiko’s girl boss characters. However, the popular 1960s series, Female Gambler (Daiei) and The Red Peony Gambler (Tōei), have not yet received much scholarly attention. This blind spot within academic understandings of yakuza film demonstrates how reliance on preexisting genre categories and casual associations, such as the association of the yakuza genre with masculinity, can lead us to overlook texts, characters, and actors prized by audiences, critics, and studios alike.

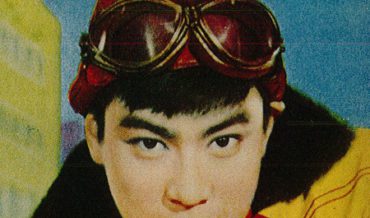

A prime example of this is Fuji Junko, who starred in yakuza films that charmed the critics of the era (Takasawa 1969, 70). Indeed, critical coverage of male lead and female lead yakuza films in the cinema press was roughly equal in the late 1960s (Kosuge 1968, 63), and positive critical comparisons between Fuji’s swordsmanship and that of the legendary Zatōichi character indicate that many female-led yakuza narratives were placed on par with male-led films. Furthermore, Isolde Standish argues that Fuji’s performances “opened up the genre to a female viewing position by specifically addressing issues of patriarchal loyalty as they applied to women” (2005, 309). On her debut, Tōei studios made much of the fact that Fuji’s father, Shundō Kōji, the principle producer of chivalrous (ninkyō) yakuza genre films, had strongly opposed her desire to become an actress. The shadow of her father stretched over Fuji’s star persona from the beginning; her first roles were dutiful daughter characters in yakuza and period films, including Thirteen Assassins (Jūsannin no shikaku; Kudo Eiichi, 1963) and Three Yakuza (Matatabi sannin yakuza; Sawashima Tadashi, 1965). However, the six-part Red Peony Gambler (Hibotan bakuto; Katō Tai, 1968–72) series propelled Fuji to the status of a household name.

Father figures were heavily present here, too, along with gendered themes. Fuji’s heroine Oryū, dubbed the “Red Peony” due to her tattoo, symbolically renounces her femininity in order to become a yakuza and avenge her murdered father. The origin story of Fuji’s star persona mirrored the narrative of the Red Peony Gambler series, in which Oryū becomes a yakuza out of necessity and against the wishes of her dead father. The centrality of the father figure to Oryū’s narrative, and to Fuji’s star persona, casts both as filial daughter characters. The Red Peony Gambler series, already at a “fever pitch of popularity” due to press coverage, even before its release in September 1968, emphasized Fuji’s filial characteristics; critics noted that her star persona, predicated on “beautiful daughter roles” in films such as Thirteen Assassins and Three Yakuza, was consistent with the role of Oryū (Kosuge 1968, 63). Even as she played Oryū in six films, Fuji continued to intersperse the series with strong daughter roles avenging dead fathers in other films, for example in Bright Red Flower of Courage (Nihon jokyōden: makkana dokyōbana; Furuhata Yasuo, 1970). (These were female entries into the chivalrous commoners of Japan series.)

Drawing on narrative themes consistent with her star persona, Fuji’s roles blurred the lines between yakuza film and melodrama, focusing on familial relationships and gender issues, including romance and the norms of female behaviors. In the Red Peony series, her character’s relationships are depicted using tropes borrowed from melodrama: love interests are sadly resisted, emotional friendships are based on the fellow suffering of other women, and small children are temporarily adopted. At the same time, the character exhibits the iron will and adherence to moral codes of the yakuza genre. In set pieces that bear “family resemblances” to the soft-core pornography (roman poruno) or the “pink” genre, Fuji’s body is both sexualized and representative of a nostalgic appeal to chaste femininity. The narrative tropes of Oryū’s tattooed shoulder and repeated fight scenes necessitate regular disrobing throughout the series; however, love interests are resisted as Oryū interprets her renunciation of female gender norms as a renunciation of heterosexual love.

In press interviews and coverage, the strong and ambitious core of Fuji’s star persona is wrapped in references to her innocence, filial position, and beauty. Fuji explicitly connected both modest femininity and the female yakuza film itself to the melodrama genre in a 1968 interview with Kinema Junpō, saying, “I want to become a melodrama actress, so I don’t want to show nudity” (Anon. 1968, 83). In many ways, Fuji’s statement sums up the delicate balance through which the yakuza film fused characterizations, tropes, and themes from other genres to create a complex “regime of verisimilitude.” Fuji’s chaste refusal to show nudity reflects the reliance on female-gendered tropes of innocence and beauty, which were central to female yakuza characterization, while her career goals, and the revelation that she demanded changes to the original Red Peony Gambler script, suggest a star persona predicated on strength and ambition. The sentimental tropes of melodrama blend with the sexualization of the pink film and the violence and austere morality of the yakuza genre to create a complex “regime of verisimilitude,” which was key to the film’s wide appeal.

The Japanese yakuza genre, particularly the case of Fuji Junko, demonstrates the shortcomings of scholarship predicated too heavily on a commitment to genre as a classificatory system. As scholars such as Neale, Stam, and Bordwell caution, by focusing too closely on whether a text or star fits our preconceptions of a genre, we risk missing the relevance certain texts and stars have for their wider publics. While “genre” is a keyword in the study of media, the concept should be used with caution. On the other hand, the skilful blend of genre influences revealed in the analysis of Fuji’s Oryū character and star persona demonstrates the use value of the concept of genre. Applying Neale’s theory of genre as process, we can see how hybrid genre texts such as the female-led yakuza film and Fuji’s star persona are first constructed by industrial genre expectations, then incorporate elements of other genres to meet and exceed audience expectations, and finally persuade critics of the text’s contribution to the genre corpus. Fuji’s Red Peony series is the perfect example of Neale’s “repetition and difference,” and at the same time, a reminder to proceed with caution when using the concept of genre for media study.

References

Altman, Rick. 1989. The American Film Musical. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Altman, Rick. 1999. Film/Genre. London: British Film Institute.

Anon. 1968. “Kōgyōkai.” Kinema junpō 481 (November 1): 83.

Bordwell, David. 1989. Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Coates, Jennifer. 2017. “Gambling with the Nation: Heroines of the Japanese Yakuza Film, 1955–1975.” Japanese Studies 37, no. 3: 353–369.

Cohen, Ralph. 1986. “History and Genre.” New Literary History 17, no. 2: 203–18.

Desjardins, Chris. 2005. Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gerow, Aaron. 2005. Kitano Takeshi. London: BFI.

Gledhill, Christine. 1985. “Genre.” The Cinema Book, edited by Pam Cook, 58-64. London: BFI.

Higuchi Naofumi. 2009. Roman poruno to jitsuroku yakuza eiga: kinjirareta 70-nendai Nihon eiga. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Kosuge Shinsei. 1968. “Nihon eiga hihyō: Hibotan bakuto.” Kinema junpō 480 (September 20): 63.

McDonald, Keiko Iwai. 1992. “The Yakuza Film: An Introduction.” In Reframing Japanese Cinema, edited by Arthur Nolletti Jr. and David Desser, 165–92. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Neale, Stephen. 1980. Genre. London: British Film Institute.

Neale, Stephen. 1990. “Questions of Genre.” In Approaches to Media: A Reader, edited by Oliver Boyd-Barrett and Chris Newbold, 460–72. London: Arnold.

Schilling, Mark. 2003. The Yakuza Movie Book. Berkeley, California: Stonebridge Press.

Schrader, Paul. 1974. “Yakuza: A Primer.” Film Comment (January–February):10–17.

Stam, Robert. 2000. Film Theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Standish, Isolde. 2000. Myth and Masculinity in the Japanese Cinema: Towards a Political Reading of the ‘Tragic Hero.’ London: Curzon.

Standish, Isolde. 2005. A New History of Japanese Cinema. New York: Continuum.

Sugisaku, J-tarō, and Uechi Takeshi. 1999. Tōei pinki baiorensu roman arubamu. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

Swales, John M. 1990. Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Takasawa Eiichi. 1969. “Nihon eiga hihyō; Nobori Ryū yawarakada kaichō.” Kinema junpō 492 (April 1): 70.

Tudor, Andrew. 1983. “Genre.” In Film Genre Reader 3, vol. 3, edited by Barry Keith Grant, 3–11. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Williams, Alan. 1984. “Is a Radical Genre Criticism Possible?” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 9, no. 2: 121–25.

Yomota Inuhiko, and Washitani Hana, eds. 2009. Tatakau onnatachi: Nihon no eiga no josei akushon. Tokyo: Shohan.