When the author of the original Moomin novels, Tove Jansson from Finland, came to Japan in 1970, she received a star reception due to the popularity of the animated television series based on the novels, but she was upset by what the Japanese studio had done to her world. In 1969 Otsuka Yasuo, the famed animator and character developer, transferred from Toei Doga animation studio to A Production to work on the Lupin III television animation series. Due to the long preproduction period for Lupin, he decided to develop an animated television program adapted from the Moomin novels. He was joined by Oosumi Masaaki as the director. The animation, which in April 1970 was transferred by production company Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS) from A Pro to Osamu’s Tezuka Mushi Pro, has never been broadcast or distributed in Finland, due to a deal the rights owner Moomin Characters struck with TMS and Zuio. In Finland, the series is considered to be a “bad” adaptation or perversion of the original concept, and in 1990–91, when the second Japanase-animated Moomin series—Tales in the Moomin Valley—was produced, the Finnish coproducers were careful to have Lars Jansson, Tove’s brother, approve all storyboards.

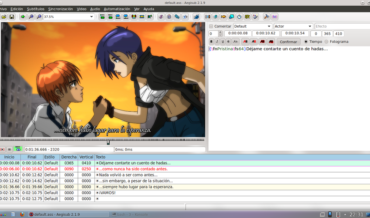

What, in fact, Otsuka and Oosumi set to do was to localize the original novels, picture books, and the four-strip cartoon for not only the Japanese family audience but also to a specified programing slot to fit Moomin to the specified needs of an episodic, weekly television animation series. “Localization” refers to the process of adapting a global/regional product for a specific market (Katsuno and Maret 2004, 82). The localization process includes translation, in the case of film and television subtitling or dubbing, or adding a local language voice-over narration. But the process does not stop with mere linguistic localization: Often the localization includes editing content, adding informative features to the program, or working out the musical soundtrack.

Localization is often close to adaptation, as the two might overlap, if the localization is part of adaptation from one medium to another. Adaptation, which means creating new versions based on original material, is central to understanding the popularity of the Moomins in Japan. As Linda Hutcheon states, adaptation is often thought to be the adaptation of literary novels into film. But, already before film was invented, the practice of adapting something—ranging from poems, plays, operas, paintings, songs, dances, and tableaux vivants—into another form was common (Hutcheon 2006, xiii).

The Moomins, a series of popular fantasy/children’s novels by Finnish author Tove Jansson, as well as picture books and a four-strip cartoon for Ny Tid (a Swedish newspaper in Finland; 1947–48) and the London Evening News (the latter coauthored with brother Lars Jansson; 1954–75), have already been adapted and localized for numerous platforms by the author herself, including theater plays and other installations. The first localization was when the novels, originally written in Swedish, were translated into Finnish—the majority language in Finland. When the Japanese anime production company TMS/Zuio decided to adapt them as the first television animation in, what was to become the decades-running Sunday evening program timeslot, “World Masterpiece Theater” (1969–97, and resuming in 2007) for Fuji TV, the animators in the subcontracting A Production studio also had to adapt the original material into twenty-five-minute television slots. According to Oosumi Masaaki, director of the 1969–70 Moomin, the team invented new storylines and localized many features of the original drawings for the 1969 Japanese animation scene.[1] Head animator Otsuka Yasuo, responsible for the character design, made the shape of the longish face rounder and redesigned the eyes to be more expressive, according to what he had learned during his long career at Toei Doga.[2]

Moomin (1969–72) was the first program in the “World Masterpiece Theater,” which sought to adapt and localize classic world children’s and young adult literature into animated television series. The series featured Heidi, Girl of the Alps (Arupusu no shojo Heiji), Anne of Green Gables (Akake no Anne), and Marco. It even featured, besides Moomin, another Finnish original work, Katri, Girl of the Meadows (Makiba no shojo Katri; original novel by Auli Nuolivaara). Therefore, the first Moomin anime was not an isolated case of Japanese adaptation but part of a concept aimed at introducing world literature to children and the whole family through television adaptations. The second Moomin series, as opposed to the Japanese production of 1969–72, was a Finnish-Dutch-Japanese coproduction, with Lars Jansson holding veto rights to any story turns and pictorial features. Seeking a global market, the production process for the second series aimed for a more flexible localization of the series for distribution to diverse national markets.[3]

Localization was a key feature of almost simultaneously developing the Japanese version and the Finnish and Swedish language versions for the officially bilingual Finnish market. Not only were the translations localized but so were the voice acting styles; the Japanese version has cuter, brighter, and higher-pitched voice acting, while the Finnish and Swedish editions have slower, lower-pitched voice actors by famous stage actors of the time. The theme music was also localized, with Japan having Shiratori Sumio’s songs, sung by his wife Shiratori Emiko, and Finland having the Benny Törnroos song in Finnish and Swedish as the theme song. Reflecting the limitations of localization to different markets with different standards, the three episodes produced in Japan were never shown in Finland, as they were deemed too violent for the standards of Finnish children’s programing. In 2016, a newly dubbed Finnish-language version was produced with new voice actors for net streaming purposes, partly due to the 1990 copyright deal with the original voice actors, which naturally did not include net streaming rights. The series has sold well worldwide, and locally dubbed versions exist in Russian, Hebrew, and Afrikaans, which was especially tricky to produce due to the racial stereotypes attached to different dialects of Afrikaans spoken in then apartheid-era South Africa. Moreover, the South African Broadcasting Corporation had to recreate much of the dialogue, as they had no access to the original script (van Staden 2010).

In thinking about adaptations as a cultural and commodity form, Henry Jenkins has theorized contemporary popular culture as working on multiple platforms, through which the consumer/viewer/fan experiences the larger story. The complete story of the work can never be gained through one platform alone. The Matrix franchise, which Jenkins uses as an example, ran through several films, an animation, and websites, which all gave more detailed information about the larger narrative world. Jenkins (2012) describes this transmedia or cross media seriality as inherent to the phenomenon of contemporary media convergence.[4] Otsuka Eiji (2001) reminds us that in the case of serial consumption (as with television animation), every single narrative episode forms a small narrative world, which is experienced by the viewer as part of the world of the grand narrative and is formulated through the series.

Adaptation’s process and final result are naturally dependent on the medium to which the original is being adapted. As Hutcheon states, an adapter working with a story is attracted to different aspects if the story is being adapted to film as opposed to opera (2006, 19). In the case of the Moomins, the medium of television animation has its own rules of aesthetic and commercial expression. The aesthetic style of expression is dependent on the technique of adaptation, which derives from the localized history and practices within the respective country’s history of animation: The Moomins have been adapted to cell animation (Japan, twice), computer-assisted cell (Finland, France, Korea), mixed-media stop motion (Poland), and will be adapted to a combination of 2D and 3DCGI in the upcoming Finnish-British animation.

The commercial expression is most evident in the merchandizing. Nowadays, Moomin goods are big business. Moomin coffee mugs for Finland-based Arabia china, designed by Tove Slotte, began production in the 1950s. When discussing the “originality” or “authenticity” of any Moomin adaptation, reference is often made to the officially licensed Moomin products, from animation to goods, museums, amusement parks, and coffee shops. The licensing is handled by Moomin Characters Inc., which is run by Jansson’s niece Sophia Jansson, the artistic director, and her husband Roleff Kråkström, the managing director. In the Japanese context, the term “media mix” is useful for understanding how the centrality of characters defines the Japanese multiplatform adaptation (Steinberg 2012, 171–203). Marc Steinberg traces the development of product merchandizing that began with Japan’s first television animation series Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu; 1963–66) and further developed by publishing/film production company Kadokawa from the mid-1970s onward. Kadokawa’s media mix strategy of marketing with popular animation was to work with the combination of manga magazines, video games, anime, and novelizations. Central to this narrative world was the audience’s relationship with the character. This began in 1963 with Astro Boy and related products (e.g., candy and stickers) and was further refined by Kadokawa as a method of marketing across media platforms. Here, the consumer faces a fragmented story world through the consumption of the character. The expressive relationship between the narrative world and the character is indispensable for the creation of animated stories (Otsuka quoted in Steinberg 2012, 179).

The media mix concept is important for understanding the prevalence of Moomin in Japan, despite the fact that the Moomin animation series was last broadcast nearly three decades ago. The Moomin story world is essentially constructed around the characters and their interactions. In fact, the first Moomin anime director, Oosumi Masaaki, created episodes around the characters and the conflicts between them, as the production had to produce twenty-six episodes.[5] However, despite the absence of a current animated series, the Moomin character-based world can be consumed through such platforms as merchandise, exhibitions (one exhibition in 2015–16 drew over 1 million visitors in Japan), cafes, travel to Finland, and so on. As Steinberg states, “the immaterial entity of the character as an abstract, circulating element that maintains the consistency of the various worlds or narratives and holds them together” (2012, 188). He points out that the most popular postwar characters in Japan—Astro Boy, Doraemon, Hello Kitty, and Pikachu—“possess large, expressive, yet vaguely blank eyes; colorful bodies often composed through the use of coinciding circles; and a hybrid child-animal appearance” (ibid., 191).

According to Moomin Characters Inc., after the 1990–1992 animation series, a large part of the Moomin merchandise was based on the animation series in terms of character design, coloring, and other stylistic features. In the markets of both Finland and Japan, there was a mix of merchandise of different styles and quality. In 2008, 85% of the merchandise was based on the second anime, and 50% of the sales were realized in Japan. Indeed, much of the merchandise was localized for the Japanese market by emphasizing the “cuteness” (kawaii) of the characters. Since Roleff Kråkström joined Moomin Characters Inc. in 2008, the company has consciously redesigned the brand image together with the BOND design agency. The new concept is based on the original Jansson art work for all Moomin merchandise—prohibiting any licensing based on the animations—and using the same font everywhere, designed by Tove Jansson in all Moomin-related merchandise and PR, ranging from the Moomin logo in the products to the website, online games, and the Moomin shop sign at the Helsinki airport.[6] In this sense, the Japanese localization has come full circle, affirming the popularity of Moomin back home in Finland.

Notes

- From the author’s interview with Oosumi Masaaki, Tokyo, Japan, December 13, 2016. ↑

- From author’s interview with Otsuka Yasuo, Saitama, Japan, December 3, 2016. ↑

- Delightful Moomin Family (Tanoshii Moomin ikka; 1990–91), its sequel Delightful Moomin Family: Adventure Diary (Tanoshii Moomin ikka: Bōken nikki; 1991–92), and a long feature film Comet in Moominland (Tanoshii Mūmin ikka: Mūmindani no suisei; 1992) were produced by Dennis Livson, a Finnish children’s program producer who had established a company in the Netherlands and had experience working with Japanese animation studios with his production Alfred J. Kwak (Chiisana Ahiru no Ōkina Ai no Monogatari: Ahiru no Kwak; 1989). ↑

- In the media industry, “media synergy” often has the same meaning (Steinberg 2012, vii). ↑

- From the author’s interview with Oosumi Masaaki, Tokyo, Japan, December 13, 2016. ↑

- The font is used, for example, on the official Moomin website: https://www.moomin.com/. ↑

References

Hutcheon, Linda. 2006. A Theory of Adaptation. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, Henry. 2012. “Searching for the Origami: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling.” In Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader, edited by Timothy Corrigan, 403–24. London: Routledge.

Katsuno, Hirofumi, and Jeffrey Maret. 2004. “Localizing the Pokémon TV series for the American Market.” In Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon, edited by Joseph Tobin, 80–107. Durham: Duke University Press.

Otsuka Eiji. 2001. Teihon monogatari shōhi-ron. Tokyo: Kadokawa.

Steinberg, Marc. 2012. Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Tuulikki Karjalainen. 2013. Tove Jansson: Tee työtä ja rakasta. Helsinki: Tammi.

van Staden, Cobus. 2010. “Mutations in Moominvalley: Globalization, Capitalism and the Cultural Identity of Fiction.” In Imaginary Japan: Japanese Fantasy in Contemporary Popular Culture, edited by Eija Niskanen, 26–29. Turku: International Institute for Popular Culture.

Williams, Raymond. 2003. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. London: Routledge.